[ 8 ]

Storyboarding for Product Design

One Document to Capture It All

Over the last few years as I’ve been coaching and mentoring teams on UX-related matters, one of the UX tools that I’ve been the strongest advocate of is experience maps. Experience maps, also called customer experience maps, visualize and capture the full end-to-end experience that a user goes through in order to complete a goal.

The benefit of an experience map is that the process of working through one, and the finished result, help you understand the full end-to-end experience and force you to think beyond the page or view that you’re working on. Experience maps are also about more than what happens on the screen. They cover the offline aspects and, if done well, show how everything is intricately linked and how a change on one end will impact something somewhere else. The more the products are services we design need to work on any device used anywhere and at any time, the more we need to be able to dip into a specific point in a user’s journey and understand what matters then and there. This is another thing that experience maps are really great for.

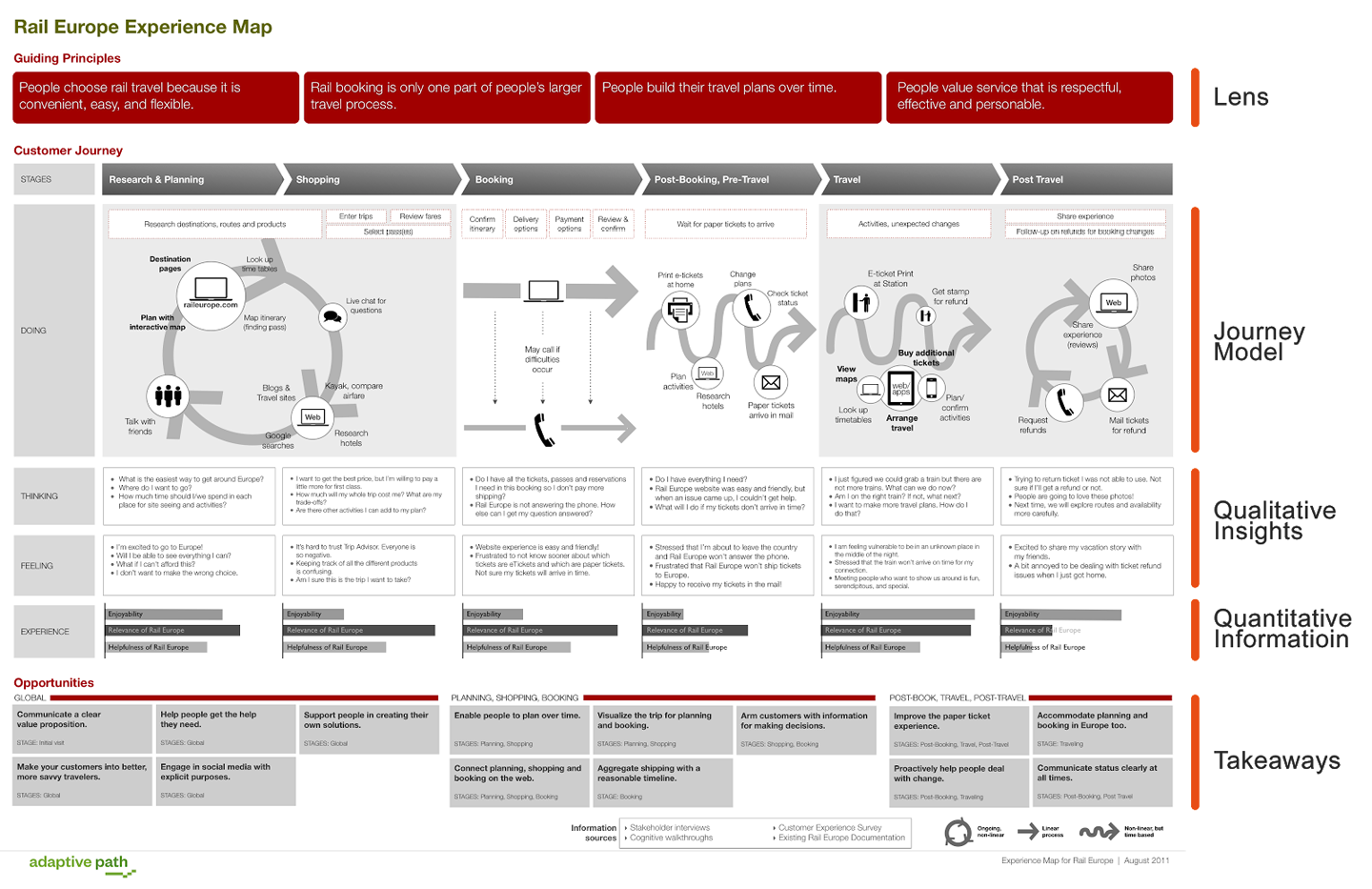

One of the most, if not the most, famous experience map is the Rail Europe Experience Map, which was developed as one part of an overall diagnostic evaluation for Rail Europe, Inc (Figure 8-1). The company wanted to get a better understanding of its customer’s journeys across all touch points in order to define where to focus design and development resources, as well as its budget. What the Rail Europe Experience Map helped to do was, in the words of author and designer Chris Risdon, “create a shared empathic understanding of the customers’ interactions with the Rail Europe touch points over time and space.”

Figure 8-1

The Rail Europe Experience Map, courtesy of Chris Risdon and Adaptive Path

The Rail Europe Experience Map holds a great level of detail for that project. To the unfamiliar eye, it’s the kind of document that some would consider complex. They are right. Experience maps are complex, but that’s because we as human beings are complex. There is no one journey or one experience of the products and services we define that will be the same as that of someone else. There will be the ideal path, and more common and likely journeys, but the story of how our products and services are used, how they come into people’s lives, and the role they play will change with every single user.

The initial reaction of many of the people I’ve introduced experience maps to is that it’s too complex and that the level of detail they hold isn’t needed for the project in question. There is no denying that experience maps, at times, can look quite complex and scare people, but the complexity that goes into creating an experience map is its beauty. When you work and talk through them, most people and teams find them incredibly valuable. They can often be one of the first steps in breaking down organizational silos.

Additionally, just as the product experiences we design are never really finished, experience maps are never really done. Rather than an end point and a conclusion, experience maps should be seen as a catalyst, says Risdon, something that is actionable and will get people talking.

One of the great benefits, and opportunities if used correctly, is that experience maps are brilliant as a do-once-and-keep-on-using kind of document. They are living and breathing documents that the team and project can derive great value from by constantly evaluating and improving, not to mention use as a reference point throughout the project as various aspects are being worked through. To make this process easier, print out the map in large format and put it up on a wall if you have access to one, where it’s easy for the team to see and get to it.

Done right, experience maps provide a snapshot of what you’re dealing with. Name one person who wouldn’t rather have one thing to look at and go “Ah!” than 10+ pages requiring them to mentally put everything together at the end. And as for how to make them look less complex, this is a matter of visual presentation and how you talk through it. Most experience maps have a visual element that captures either touch points, as shown in Figure 8-1, or the emotional flow that the user will go through. Another opportunity is to include a storyboard as the visual element.

The Role of Storyboarding for Film and TV

Storyboards are linear sequences of illustrations used to visualize a story. They were made popular in the form they are known today by Walt Disney Studios in the 1930s. Since the 1920s, Disney Studios used sketches of frames to help create the world of the films before they actually began building it. Disney was also the first to have a specialist story department that was separate from the animators. This department was introduced as Disney had realized that audiences wouldn’t care about the film unless the story itself gave them reason to care about the characters.

Storyboards are commonly used in films, theater, and animatics. In theater, storyboards are used as a tool to help understand the layout of the scene. In films, they are also known as shooting boards and often include arrows to indicate movement as well as instructions. Storyboards play an important part in helping the director, cinematographer, and advertising clients visualize the scenes. For the live-action filmmaker, they also help in identifying which parts of the set needs to be created versus which parts will never come into the shot. Using storyboards for films also helps identify any potential problems before shooting begins, as well as estimate costs. In this sense, storyboards can be seen as the low-fidelity prototype of a film.

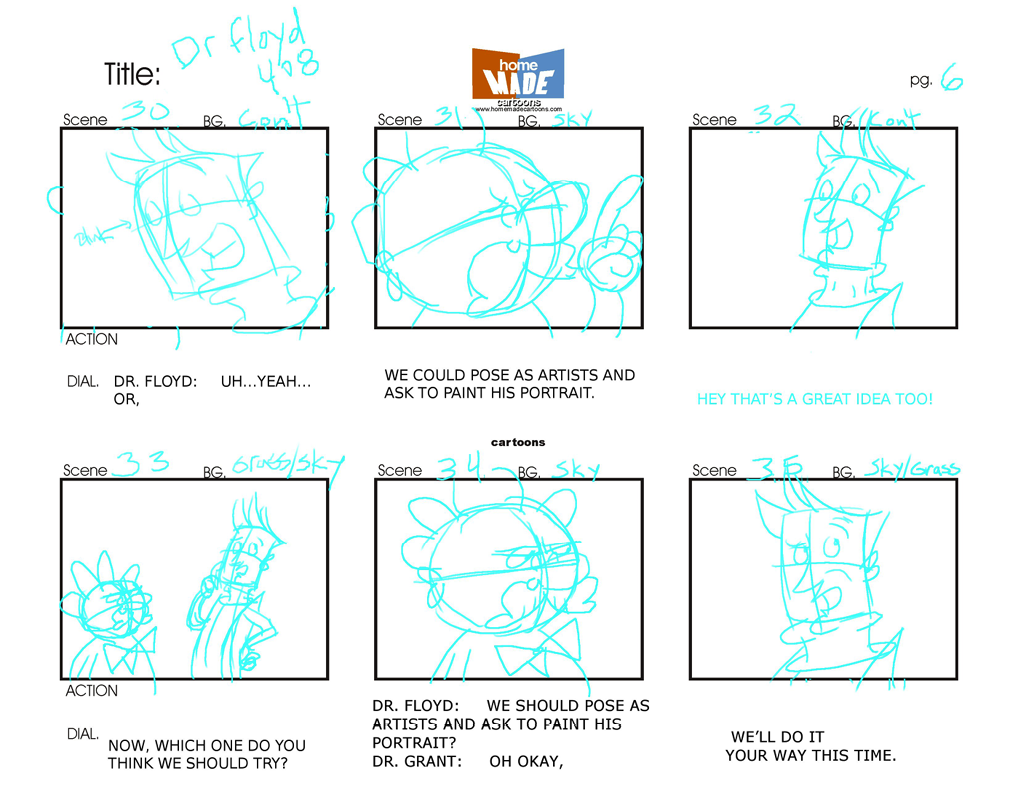

In animations and special effects, storyboards are often followed by animatics (Figure 8-2). Animatics are simplified mock-ups that are created to develop a better idea of how a scene will look and feel when motion and timing have been added. In its simplest form, an animatic is made up of a series of stills, usually taken from the storyboard, and new animatics may be added until the storyboard is complete. Just as in films, the storyboards and animatics help ensure that time and resources are used well instead of being spent on scenes that may end up being cut from the film later. In computer animations, the storyboards also help identify which parts of the scene components and models need to be created.

Figure 8-2

Storyboard for The Radio Adventures of Dr. Floyd (https://oreil.ly/HrYMH)

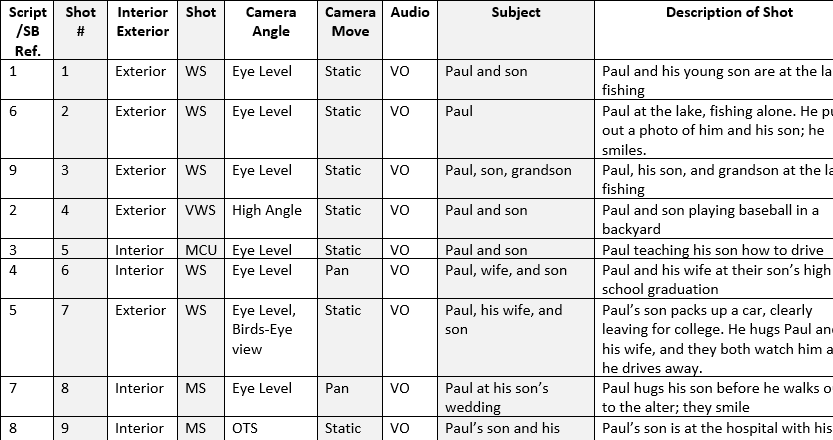

To what level of detail the storyboards are followed during production varies. Some directors use a storyboard as a reference point together with the script, from which a detailed shot list is created. A shot list is a document similar to the one in Figure 8-3 that maps out all the shots, together with who and what will be included.1 Such a document is particularly useful when a film is shot in multiple locations, as it helps directors to organize their thought before filming begins. For this reason, creating the shot list usually done in conjunction with the script and other activities in the preproduction process.

Figure 8-3

Screenshot of a shot list template from the TechSmith Blog

Exactly how storyboards are used in preproduction and production varies. Pixar, for example, doesn’t begin a new movie with a script but instead starts with a storyboard.2 Others follow a script–storyboard–shot list path, and what’s in the storyboards may change after they are done. On the other end of the spectrum, productions treat the storyboards as a bible. The film The Matrix is an example of this. To convince the suits at Warner Bros Entertainment to buy the script, the Wachowski sisters hired two underground comic book artists named Geof Darrow and Steve Skroce to draw up a shot-by-shot storyboard of the script, something that ended up being six hundred pages. During the filming they didn’t allow the director to deviate from the storyboards, except during the editing process.3

Whether the storyboards are used as a way to help define the narrative, or are seen as an end product, there are a lot of overlaps and benefits of storyboarding for product design.

The Role of Storyboarding in Product Design

During my career as a UX designer, I’ve worked with a lot of digital and full-services marketing agencies. In those companies, storyboarding has often been carried out by the creatives in concepting as part of the process of coming up with and selling ideas to the rest of the team and the client. Very seldom have I seen it being used by any UX or product team. However, I’ve come across many other companies that use storyboards as part of the UX and product design process, including Airbnb and The Atlantic. This is great as the benefits of using storyboards for product design is very similar to the benefit of using storyboards in theater, film, and animatics.

Just as in theater, film, and animatics, through storyboarding you start to explore the world in which the experience will take place, and you start to explore the structure. By storyboarding parts or the whole experience narrative, you both explore and define the experience the user has with the product, and the aspects that matter around it. By adding emotions and making it come to life through the drawings, you both visualize and help create empathy, understanding, and buy-in within the team as well as stakeholders and clients. And just as with film and animatics, storyboards as part of the product design process are a great tool for spotting gaps or new opportunities, as well as to help determine costs and identify what you’ll need.

Here are some of the other reasons that make storyboards so great:4

- Help you understand the problem space you’re working with

- Bring a solution to life

- Are an effective communication tool that almost anyone understands and can engage with

- Combine multiple elements, such as personas, behaviors, requirements, and solutions

- Make conceptual ideas tangible, which helps us, clients, and stakeholders to connect the dots

Just as storyboards are used in various ways in theater, film, and animatics, they can be used in various ways in product design as well. We’ll cover some of those ways a bit further ahead in this chapter. No matter how they are used, however, just as experience maps are great as a team activity, or for involving different parts of the business and/or the client, storyboards are equally great as something that not just one or two people work on but that instead include various people. By collaborating on storyboards, you help create buy-in, understanding, and empathy. Because each storyboard can be related to a specific persona, it helps to continuously ensure that the people the product is for are actually considered.

Using Storyboards to Help Identify the Invisible Problem and/or Solution

When you start to storyboard an experience related to a product, the simple act of having to draw it requires you to include a lot of things in order to make the narrative come to life. Having to think about the experience in this narrative way is what led Airbnb to its big insight: that its service isn’t a website, as most of the Airbnb experience in fact happens offline.5

Far too often we jump straight in, thinking that we have a solid understanding of the people we design for and the content, features, and overall solution that will best meet their needs. And hopefully we do. However, as offline and the dance, as the Airbnb team refers to it, between offline and online experiences increases for a large number of products and services, there is also an increased need to take a step back and create an actual picture of the overall experience that different parts of the team, the business, and the client can engage with. It’s no longer enough to just have the UX or product team working on experience maps or storyboards. To create really great products that best incorporate both user and customer insight, as well as business requirements, we need the different parts of the business to come together and for everyone to share their knowledge and expertise.

Tony Fadell, one of the originators of the iPod, says that “as human beings we get used to things really fast” and that as a product designer it’s his job to see those everyday things and improve on them.6 The reason we have to get used to everyday things is that, as human beings, we have limited brain power. To deal with this, our brains encode things we do on an everyday basis into habits, using a process called habituation. This process allows us to free up space to learn new things, and what’s originally hard becomes easier and easier until it’s eventually second nature and we’re able to relax more by thinking less about what we’re doing.

Fadell says driving a car provides a good example of habituation. When you first start driving a car, you pay close attention to the ten-to-two position of your hands, turn off music or the radio, and limit talking and anything else that might distract you from what you’re doing. Over time we become more used to driving. Our ten-to-two grip loosens up, we start to listen to music or the radio at the same time, and even talk to the passengers in the car. In these instances, habituation is good. Without it, we’d notice every single little detail, all the time.

Habituation is not a good thing when we stop noticing the problems that are around us. Our job, Fadell says, is to go one step further and not just notice the problems, but fix them. To do that, Fadell tries to see the world the way it really is rather than the way we think it is. Solving problems that almost everyone sees is easy, but “it’s hard to solve a problem that almost no one sees.”

An example of solving a problem that almost no one sees is the “charge before use” label that used to come with the electrical products we bought. Apple and Steve Jobs noticed it and said that they weren’t going to do that. Instead, the battery of Apple’s products came partially charged. Today, that’s the norm for most products. The importance in this story, Fadell says, is that it sees not only the obvious problem but the invisible one.

Fadell’s advice for noticing all the invisible problems is to first look broader and examine the steps that lead up to the problem and all the steps that come after. Second, look closer at the tiny details and ask whether they are important, or are simply there because that’s the way we’ve always done it. Last, think younger—be more like kids and ask the optimistic, problem-solving questions like the one Fadell’s daughter asked: why doesn’t the mailbox just tell us when there’s mail rather than us having to walk out each day to check it?

Storyboarding is a great tool for helping spot these invisible problems, or solutions. Through the act of creating and bringing the narrative of specific personas to life, we start to see the experience through the user’s eyes. The act of drawing itself is also usually a fun activity that lowers people’s guards and allows you to have a bit of “what if...” with it. In the world of stories, anything is possible, and adding that dimension to the product design process helps us see things in a different light from what we’re used to.

Creating Storyboards

Some people will be put off by the idea of storyboarding simply because they don’t think that they can draw. However, there are a number of ways to draw, and if you don’t feel comfortable drawing, perhaps someone else who’ll be part of the storyboarding process does. There are other ways to contribute to the storyboarding process besides drawing, from helping define the purpose of the storyboard (e.g., whether it’s carried out to help think through an experience or a communication tool), to identifying all the elements and details that should go into it.

In 2011, UX writer Ben Crothers did a three-part series around storyboarding and UX for the Johnny Holland blog. The second part, which focused on how to create your own storyboard, shared some useful advice: while storyboarding can be used for ideation, just as it is in concepting and at times for Pixar, you’ll get the most out of your storyboards and storyboarding process if you first have a clear point of view. If you’re going to use storyboards for ideation or as a thinking exercise, you will get the most out of the exercise if you’re clear on who the storyboard is about and what goal that character, or user, has.

Crothers continues to advise that if you’re going to use storyboards as a communication tool, it helps to be clear on what you’re communicating. More precisely, if you’re using your storyboard, do the following:7

- Solve an existing user experience problem

- Identify the impact of an existing situation or issue on the user experience

- Define a desired user experience for a particular solution

These three scenarios apply, in my opinion, if you’re using your storyboards as an ideation or thinking tool too.

Once you have a clear point of view, the next step is to identify the story structure. You may choose to do a high-level end-to-end storyboard for the full experience, similar to the shopping experience we covered in Chapter 5, or you may choose to do it for a specific journey, or sequence, as we referred to it earlier. If you’ve carried out some of the exercises in Chapters 5 or 6 related to narrative structure and character, you’ll have plenty of your narrative already defined and it’s just a matter of bringing it to life.

In terms of what to include, Crothers recommends that you include the following, which is inspired by Aristotle’s seven golden rules of storytelling:

Character

The user or customer personas that the plot is about

Script

Aristotle refers to this as diction, is the inner dialogue that the character is having, what they say, and what others around them say

Scene

The scenario that the character finds themselves in

Plot

The narrative that unfolds in relation to your character’s goal

In addition, you can add the environment or setting of the scenario and the solution.

Ways to Incorporate Storyboards into the Product Design Process

As we covered earlier, the role of storyboards and to what level of detail they are followed varies in traditional storytelling, all depending on what is being created and who is working on it. As with all deliverables and tools, when it comes to the UX and the product design process, it’s about choosing the one that is best for the job, including the team, and about using it for what the deliverable and tool itself is great for. While storyboarding can be a great activity to include, for example, developers in, that doesn’t mean that storyboards should substitute other deliverables like flow charts that developers are used to working with.

Every deliverable and tool has its own part to play, at a specific time, during the product design process. Next we’ll look at three ways that storyboards can be included in the product design process.

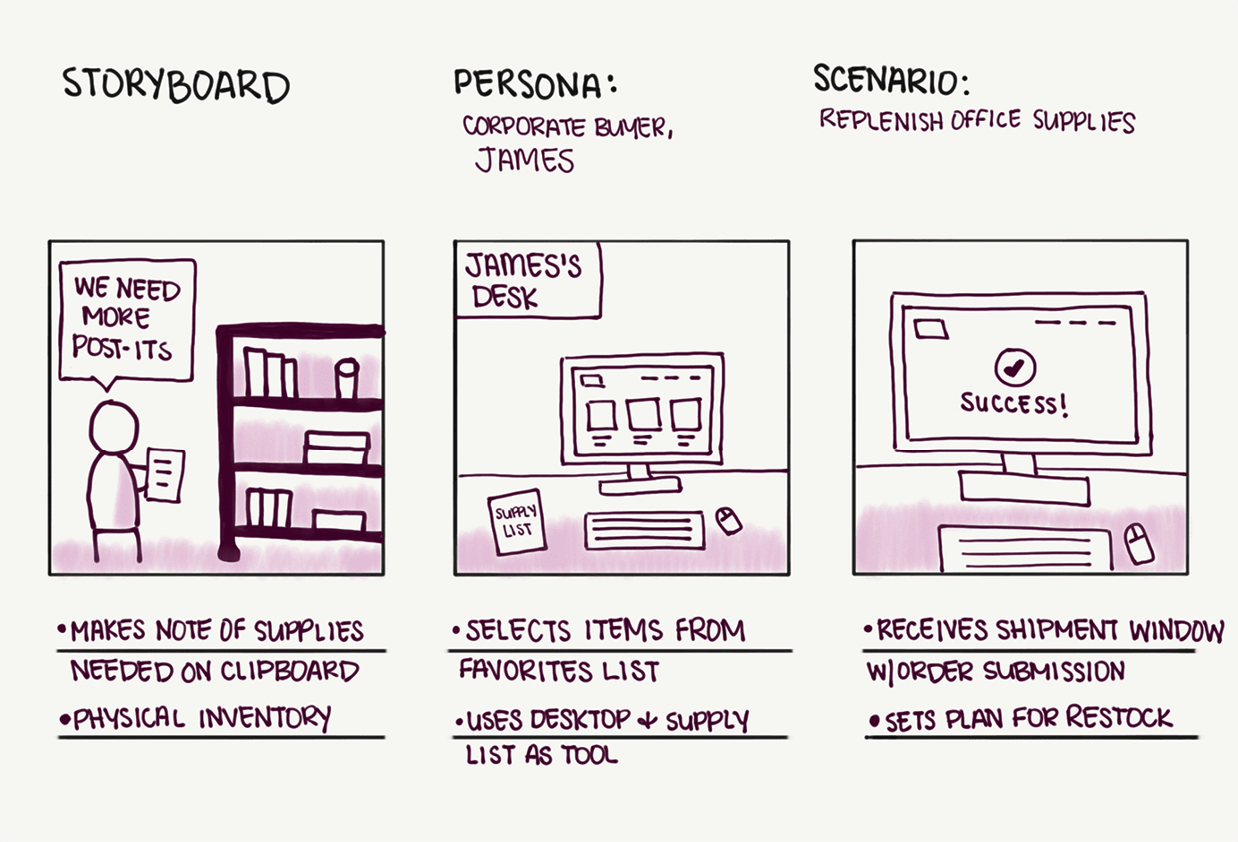

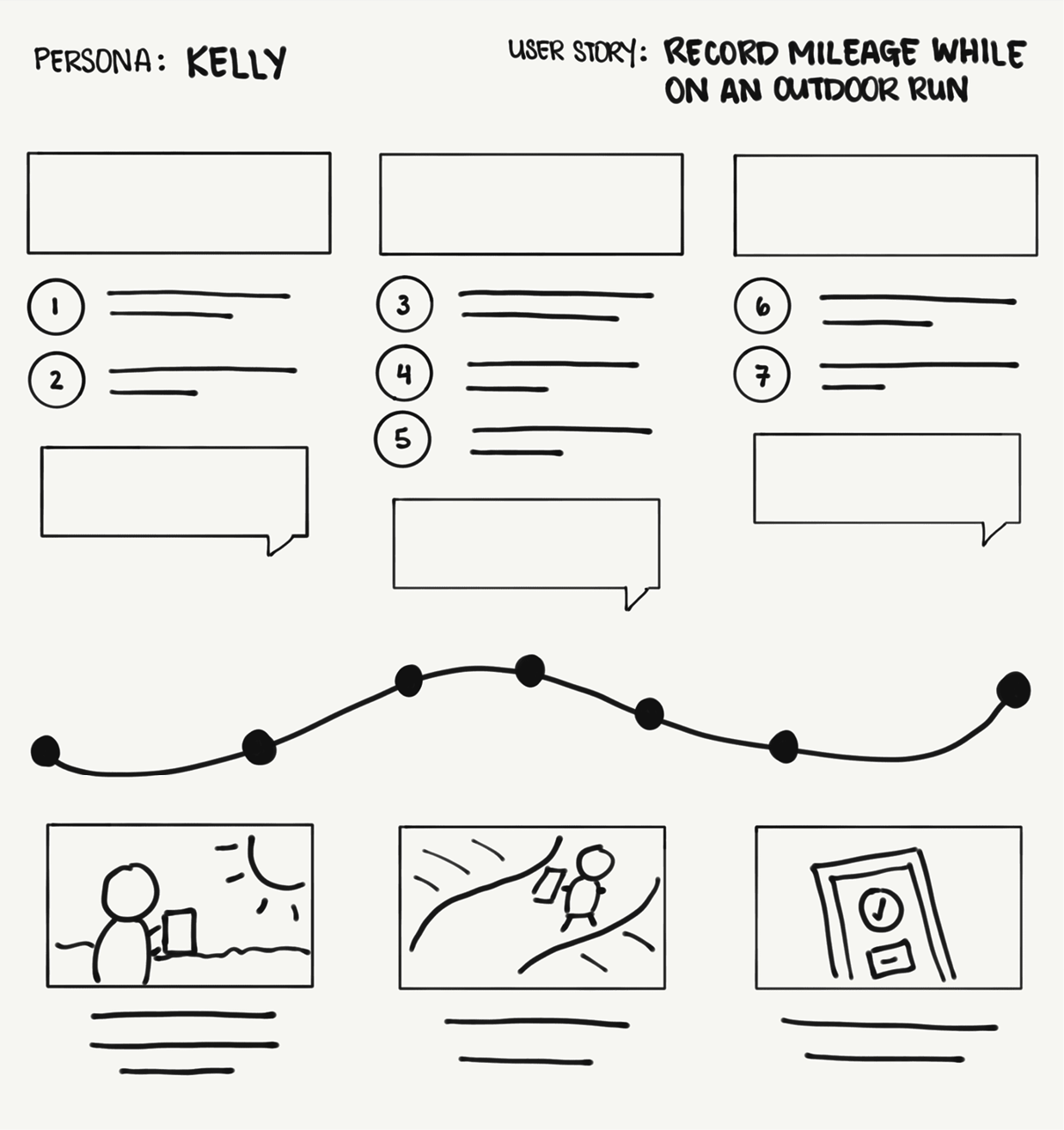

Storyboards as Their Own Deliverable

For comics, storyboards are seen as the end product rather than the means to an end. But even if storyboards will never be the end product in product design, they can be the end product in the sense of them being their own deliverable (Figure 8-4). It all depends on what you include and why.

As we covered earlier in this chapter, you’ll get the most out of the storyboarding process if you’re clear on the purpose of the storyboard and its point of view. Using storyboards as their own deliverable works well both when they are used as a thinking tool and a communication tool. The key is to identify what the storyboard should capture, with regard to the overall narrative and any additional details and notes that you may want to add in order for the storyboard to be as valuable as possible to the project, and the people who will refer to it.

Figure 8-4

A low-fidelity storyboard created as its own deliverable by Rachel Krause, “Storyboards Help Visualize UX Ideas” NN/g, https://oreil.ly/7ttZg

Storyboards as Part of Customer Journey Maps

Earlier in this book, we covered customer journey maps as a common tool for capturing the user’s emotional response to part of an experience. As with most (UX) deliverables, you get the best outcome and value when you customize and adapt that deliverable to your need. The internet is filled with various takes of what they can include and how they can be visualized. One take on a customer journey map is to further add to it by including a storyboard that helps bring the narrative of the experience to life (Figure 8-5).

This can be done in numerous ways, depending on what information you need to add to best further the project. As the example in Figure 8-5 shows, you can use just a few visual elements if that is all you need to get the key point across.

Figure 8-5

A storyboard (bottom) is included as an additional visual element in the customer journey map (top) by Rachel Krause, “Storyboards Help Visualize UX Ideas” NN/g, https://oreil.ly/7ttZg

Storyboards as Part of Experience Maps

Just as storyboards can be included as an additional element to customer journey maps, storyboards can also be added to experience maps. The storyboard could be the main visual element (i.e., the user journey representation) or an additional one.

According to Adaptive Path, there are four overarching steps for mapping experiences:8

Uncover the truth

Study customer behavior and interactions across channels and touch points.

Chart the course

Collaboratively synthesize key insights into a customer journey model.

Tell the story

Visualize a compelling story that creates understanding and empathy.

Use the map

Follow the map to new ideas and better customer experiences.

With regard to the fourth point—use the map—one of the strengths of customer journey maps is that they can be adapted to best fit the needs your specific project. In Mapping Experiences (O’Reilly), James Kalbach provides an extensive account of the process involved with mapping experiences as well as examples of what they can include and look like. A simple search online will show many takes on what detail and what type of visual to include. The more captivating the visual, and the experience map as a whole, the more favorable other people tend to be toward getting involved.

Summary

In the words of Fadell, our challenge is to “wake up every day and experience the world better.” By taking a step back, thinking and working through experiences end to end, we help create the best possible conditions for noticing and capturing the kinds of problems and opportunities that no one else sees and turning them into something great. This is about making sure that we don’t stop at a certain point (e.g., purchase), but consider the needs of the user as well as the business throughout the full product life cycle, and even before it officially begins by looking at the user’s backstory.

What we might even set a new standard, just like Apple’s charged products did. While leaving a lasting legacy that influences how other companies do things would be nice, it shouldn’t be our goal. Often it’s the little things that make a big difference. Just as Walt Disney acknowledged that small details are what make a story come together, paying attention to minor elements of product experiences is how we’re able to define problems and opportunities, and deliver value and products that really work for our users, and as a result, positively impacts our bottom lines.

Doing this requires that we bring the experience to life for everyone that is involved with working on the product—using a storyboard as its own deliverable, or as part of a customer journey map or experience map, or just through the use of an experience map. Whatever format it takes, these types of tools and outputs help ensure that we’re being more explicit and take that holistic end-to-end approach that brings different aspects of the product experience to life, creating more empathy and understanding for the end users’ situation in the process.

1 Justin Simon, “How to Write a Shot List,” TechSmith. https://oreil.ly/Y44kH.

2 Ben Crothers, “Storyboarding & UX: Part I,” Johnny Holland (blog), October 14, 2011, https://oreil.ly/UvmuA.

3 Mark Miller, “Matrix Revelation,” Wired, November 1, 2003, https://oreil.ly/7If-y.

4 Crothers, “Storyboarding & UX.”

5 Sarah Kessler, “How Snow White Helped Airbnb’s Mobile Mission,” Fast Company, November 8, 2012, https://oreil.ly/DmuSp.

6 Tony Fadell, “The First Secret of Design Is...Noticing,” TED2015 Video, March 2015, https://oreil.ly/CK4eg.

7 Ben Crothers, “Storyboarding & UX: Part II,” Johnny Holland (blog), October 17, 2011, https://oreil.ly/oqF4G.

8 Patrick Quattlebaum, “Download Our Guide to Experience Mapping,” Medium, February 7, 2012, https://oreil.ly/FLjPm.